Share

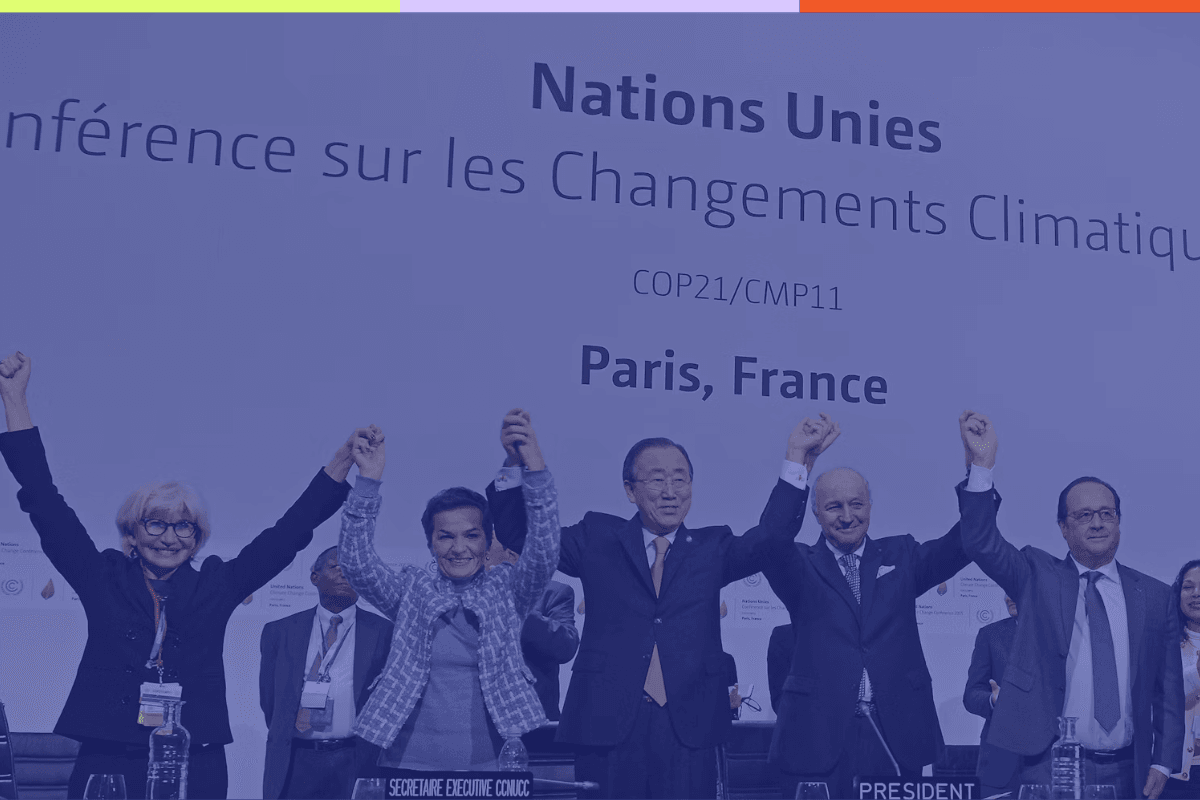

Today marks ten years since the Paris Agreement was gavelled, a moment that still shapes climate diplomacy today. Because for the first time, all countries developed and developing alike, committed under a single legal framework to address climate change. This replaced the rigid North–South divide and reflected a more multipolar, responsibility-sharing world. As we reflect on a decade since Paris, GWL Voices makes one simple, non-negotiable claim: there can be no credible climate action without women.

Paris set direction: decarbonization, cooperation, a framework for national ambition. But it was always only the start. Ten years on, the math and the lived experience tell the same story: We are behind, emissions continue to increase and the cost of delay is measured in lives, homes and the loss of ecosystems as stated in the COP30 outcomes.

COP30 produced concrete gains that matter: a new climate change and Gender Action Plan that places women’s agency at the center of its implementation a political package in Belém with ambitions on adaptation finance and NDCs, a roadmap for meeting developing countries' financing needs, new forest finance vehicles and stronger recognition of Indigenous and local communities in decisions that affect the world’s tropical forests. But even when the outcomes are progress, it is not yet the pivot we need.

GWL Voices has argued that climate policy is weaker if it ignores gender. Women are disproportionately affected by climate impacts, yet they lead effective solutions at community, national and global levels. COP30 elevated the gender agenda: Parties agreed on the Belém Gender Action Plan and pushed gender-responsive finance and programming into the center of implementation discussions. This is not a side issue: integrating gender transforms outcomes, improves fairness, and accelerates implementation.

From commitments to implementation: The next decade must be different

Paris set the direction; Belém has begun to assemble tools. The test now is implementation, and that means three practical shifts:

- Finance that reaches women and communities: Climate finance must be gender-smart, this means being accessible, accountable, and designed with women leaders and Indigenous peoples as partners, not recipients. Belém’s new facilities and pledges are a good first step in this direction.

- Institutional change and participation: Women must sit at every table where climate decisions are made, from local forest councils to national finance ministries to global funds. Participation without power is tokenism and GWL Voices will continue working on increasing women’s leadership and participation in climate action.

- Gendered monitoring and accountability: National plans (NDCs), adaptation programs and loss & damage funds need gender indicators and community-level reporting so we can see who benefits and who is left behind. During COP30 it was clear that there is still much work to be done to reach the proposed goals (See GWL Voices’ analysis on the NDC’s and gender).

No climate justice without women

GWL Voices’ mantra is simple: there is no climate action without women. When women lead, programs are more equitable and more likely to succeed. When women are excluded, policies fail to reach the scale or justice required. COP30 showed the world is beginning to accept that truth, now we must finance it, legislate it, and build it into every implementation plan.

At GWL Voices we advocate for a gender-equal international system, including multilateral organizations working on climate. We collect data to make evidence-based advocacy and initiatives with highly experienced members such as GWL Voices members: Christiana Figueres, Mary Robinson, Maimunah Sharif, Patricia Espinosa, María Fernanda Espinosa, Rachel Kyte, and Flavia Bustreo, just to mention some. These women continue advocating for women’s representation and leadership in climate action, proposing applicable and effective measures, like GWL Voices’ Four Asks for COP30.

A decade ago, Paris created a plan. In COP30, Belém renewed the urgency, provided new tools, and gave a clear lesson: progress will be partial unless it centers women from the start. The next ten years must be about implementation, and about political will that matches the scale of the crisis. Change is possible when women lead.